Speaking at an event run by The Consumer Goods Forum, Amcor’s Sustainability Director Dr. Gerald Rebitzer examines whether packaging and the circular economy can ever co-exist.

In October at the Sustainable Retail Summit, I asked a simple but profound question: can plastic packaging and the circular economy ever co-exist?

Insights from my conversations with brand owners and retailers

Talking at the Summit with sustainability experts, retailers and brand owners from across the globe, several recurring themes were apparent. The need to tackle food waste is fast becoming one of the most urgent sustainability challenges for the consumer goods sector; around a third of food produced for human consumption every year – approximately 1.3 billion tones – gets lost or wasted. Such waste is unacceptable given that 821 million people suffered chronic food deprivation in 2017.

The climate change impact caused by this wasted food equates to 11%[1] of global annual carbon emissions, on par with global emissions from cars, trucks, airplanes, trains and ships. This waste represents a pressing environmental and social concern.

Conversations at the Summit also covered the debate about tackling plastic waste. Proposed solutions often center on banning plastics, but it was acknowledged that while this may reduce plastic waste, it would have the unintended consequence of more food waste as well as higher carbon emissions from alternative packaging materials.

When it comes to plastic alternatives, there was unanimous agreement that glass and metal are generally unsuitable replacements. Despite being easier to recycle in current recycling streams, glass and metal alternatives often have a larger carbon footprint because they’re energy intensive to produce, and less efficient to transport. In contrast, plastic packaging usually has a lower carbon footprint, so here the focus needs to be on “end of use” scenarios that are more sustainable. We need to put more emphasis on the widespread collection and recycling of bags and pouches, and other packages, and move to material alternatives such as responsibly sourced bio-based plastics, which can reduce the carbon footprint even further.

We also discussed one of the biggest confusion creators in the debate on plastics: the lack of clarity around the term “single-use” plastic. Plastic food packaging for instance is far from single-use because it is used to portion, protect, transport, store and dispense food products over a period of time. This is not the same as a drinking straw or a coffee cup lid, which may be used only momentarily and then thrown away.

Busting myths around packaging

In addition to confusion about “single-use” plastic, we explored some of the most widespread myths about plastics and examined why they are misplaced.

MYTH ONE: Banning the use of plastic in packaging is the best way to alleviate plastic pollution.

Plastic is a high-performing material and ensures protection for a range of applications across the likes of medical, pharma, food and beverage, so that they’re safe for end consumers to use. And when designed well, this is with minimal material use and low carbon footprint. Currently, there is no quick and easy substitute for plastics that is free of significant drawbacks, such as increased food waste, loss of product protection, or increased packaging carbon footprint.

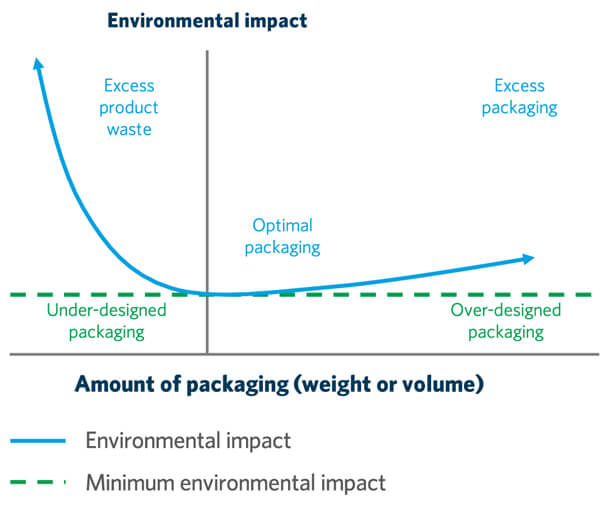

Actually, packaging needs to be balanced with protection: insufficient packaging increases food waste, which means carbon efficiency falls because more carbon is embodied in the food itself vs the packaging (in most cases, less than 5-10% of the carbon footprint of a packaged food product is related to the packaging). Brand owners and retailers need to optimize packaging for shelf-life, freshness, and supply chain efficiency while using the least amount of packaging material to achieve this.

MYTH THREE: Mono-material plastic packaging is the most sustainable.

This is typically untrue because using a pure mono-material for products such as food and medical goods, where protection from oxygen/humidity and sterility is paramount, would necessitate packaging materials that are several centimeters thick (vs. material thickness in the

Collaboration among the whole supply chain

Focusing on the theme of the discussion, “Can packaging and the circular economy ever co-exist?” I believe the answer is: Absolutely. But collaboration is critical if we are to develop advanced packaging that is as resource-efficient as possible, that protects products and keeps perishable goods safe and fresh, while minimizing food waste.

But this is only part of the solution – we need systemic change in order to establish a circular economy model and design waste out, including new strategies to enhance the collection and recycling of plastic packaging. Achieving such far-reaching change requires the participation of everyone in the value chain: raw material producers, packaging manufacturers like Amcor, industry bodies like The Consumer Goods Forum, retailers, brands, food and beverage producers, NGOs, government, collection and recycling organizations, consumers, and many others.

Packaging advice for retailers and brand owners

Retailers and brand owners in The Consumer Goods Forum and beyond need to develop packaging strategies that consider ways to reduce waste from plastic packaging, while being careful not to under-design packaging as this has the potential to increase food waste.

Here are my recommendations for retailers and brand owners:

- Engage with your packaging manufacturer early in the packaging design and innovation process to provide improved packaging options as well as sustainability advice, including science-based life cycle assessments of packaging options.

To create more alignment along the complete value chain, engage with organizations focused on developing waste and recycling strategies, such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s New Plastics Economy, CEFLEX (Circular Economy for Flexible Packaging) in Europe, and MRFF (Materials Recovery for the Future) for brands based in North America.

- Capitalize on circular economy initiatives and conversations at industry events by bringing these people and organizations together. A collaborative approach is the most effective way to devise strategies for improving waste collection and recycling, and for engaging, educating and motivating consumers about re-using and recycling their waste.

- Help consumers identify and choose products with more sustainable packaging. For example, Method’s liquid laundry detergent packaging is made from 100% post-consumer recycled (PCR) plastic, which significantly reduces the lifecycle energy consumption and carbon footprint, and fosters recycling at the same time. Bio-based polyethylene for instance can also bring sustainability improvements.

[1] IPCC 2014, Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. (the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change)

To continue the conversation with me, contact [email protected] or connect on LinkedIn.

This post was written and contributed by:

Dr. Gerald Rebitzer

Sustainability Director

Amcor